7.11 SIGNATURES

7.11 SIGNATURES

***************

The study of signatures as a key to individual traits is almost a study in itself, and is worthy of close attention. Often, a signature is more revealing than a paragraph of regular handwriting. This may seem surprising, considering its brevity, but the point is that a person puts more concentrated thought and effort into a signature than in ordinary writing.

Thus the signature becomes the individual’s trademark, so to speak. Many signatures have been traced through the years, showing how the signer has matured, implanting his personality more firmly in the final example, thus making a detailed analysis possible from comparatively trifling clues.

The usual rules of handwriting analysis can be applied to signatures where appropriate, but with certain modifications. Two of these are rather obvious. First, a signature is a formal piece of writing, and therefore may be somewhat stylized; second, a flourish may be added to give it individuality, or completion, much as an exclamation point might be put at the end of a sentence for emphasis!

Such features should not be disregarded; on the contrary, they provide some of the best possible clues to character, the sort not often found in ordinary writing. It must simply be borne in mind that slight affectations are both allowable and expected in signatures, and therefore should be interpreted in their own right.

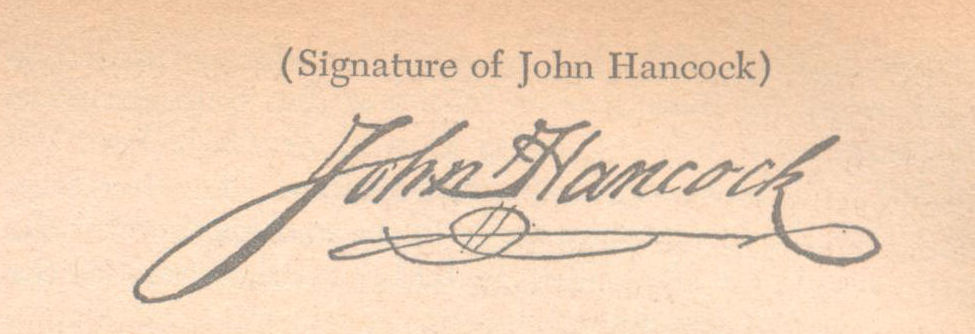

The quickest and most effective way to cover this is by a study of some well-known signatures, stressing their salient points and giving due notice to their embellishments. Good examples are found among the signers of the Declaration of Independence, staring with the name at the top of the list:

By far the largest of all the signatures, taking twice the space of any other, this shows an active nature with the eagerness to sway others. Its self-reliance looms to self-importance, with grand ideas but strict integer , these being signified by overly large writing.

Virility is stressed by the huge loop of the “J” below the line. The forward angle indicates a generous nature, looking toward future happiness and prosperity, but the ornate style shows self-sufficiency, with its natural pride accentuated by the large last letter.

The final flourish embodies several features: The straight line indicates pride of personality; the added backstroke shows an energetic fighter, but the curved lines supply a certain decree of tact.

These observations fit the personality of John Hancock, one of the most aggressive spirits of the Revolution, capable as President of the Continental Congress, yet described as a man of “vanity” and “jealous disposition” despite his ardent patriotism.

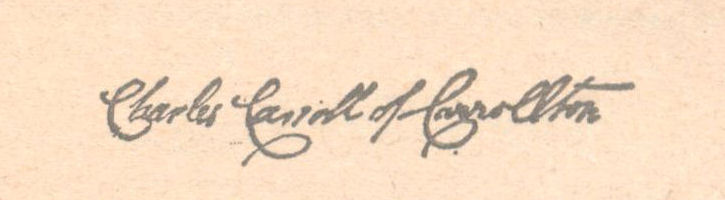

In the graceful capital letters, we see an interest in new ideas and their advancement, plus a self-importance because of their size, but tempered by self-sufficiency, as indicated by the long loops below the line. There is pride in the extension of the capitals beneath the letters that follow, but being part of a compact signature, it is not an affectation as in ordinary writing.

Instead, it stresses the forthright patriotism that caused Charles Carroll to add “of Carrollton” to his signature. One of the wealthiest men in the Colonies, he was risking a huge fortune on the success of the Revolutionary cause and he added the name of his estate, Carollton, so there would be no mistake as to which Charles Carroll had been bold enough to sign the Declaration.

The low curlicue adds the unpredictable element suited to his exact mood, for there was no telling at that time just what would become of either Charles Carroll or Carollton. All turned out well, however, for Carroll outlived the other fifty-five signers of the Declaration and still showed his urge for the advancement of new ideas when he laid the cornerstone for the B & O Railroad at the age of ninety.

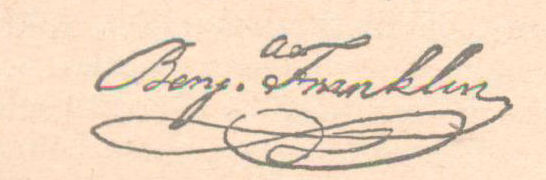

This signature is characterized by the forward slant of generosity and purpose. The “j” of “Bnenj” ends in a high curlicue, showing love of nature and simple things, while the high “k” and “l” reveal an emphatic personality, being just sufficiently rounded to account for Franklin’s keen wit.

The roundish tendency throughout shows a devotion to duty, a desire for harmony, and an appreciation of comfort, all of which characterized Franklin. But most remarkable of all is the fact that this comparatively simple signature should be embellished with the intricate flourish that appears beneath it.

This “knotted flourish,” as it is sometimes styled, had long been recognized as the mark of the firm but tactful negotiator, the symbol of the true diplomat. Franklin was noted for such qualities, more so than any other signer of the Declaration, and none of the others begin to match his flourish

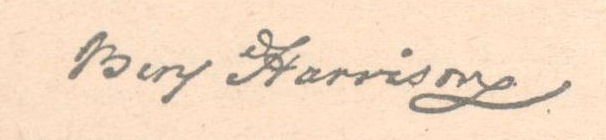

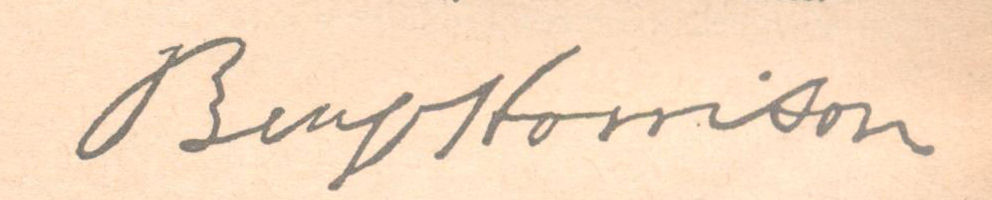

Here, the “open” capital B shows a frank, outspoken nature. Compared to an assumed modest in Franklin’s abbreviated “Benj” with its offsetting curlicue, the “Benj” of Benjamin Harrison is totally unassuming and therefore more genuine.(see footnote)

In contrast, there is self-importance in the ornate capital H. The isolated capitals show strong independence, the “r’s” of the printed type give power of expression, and the spacing between the letters indicates good judgment of human nature. Harrison had such qualities, for he was speaker of the Virginia legislature for three years and was three times elected governor of the state.

The final flourish gives further contrast to the first and last names thereby denoting pride to the extent of great egoism where family is concerned, judging from the way it carries beneath the name, then finishes with an extended sweep, as though leaving it for future generations to tell.

If any man had a right to such opinions that man was Benjamin Harrison for both his son and his great-grandson were elected to the Presidency of the United States.

As a striking comparison in handwriting analysis, here we have exactly the same name, even to the abbreviation of “Benj” for “Benjamin,” in the signature of Benjamin Harrison, twenty-third President of the United States and the great-grandson of the signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Here, again, there is frankness in the open B, but the narrow H shows a retiring disposition. The abbreviated “Benj” with its open “j” could show the acceptance of tradition.

The real contrast begins with the connected capitals, showing cooperative effort rather than Dependent action. All the letters, including the names, are connected, emphasizing a positive, decisive nature. The ending is emphatic, signifying a fulfillment with its very slight downward slant. The angular writing symbolizes leadership and the “printed” r’s carry the same power of expression shown by the earlier Benjamin Harrison.

Considering the signatures of older famous persons, we have:

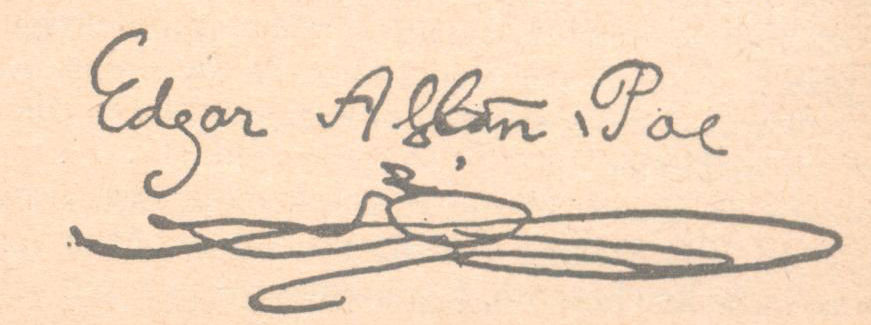

Here there is a mingling, running from simple E, through printed A, to somewhat ornate P. These in themselves show both a versatile and indecisive temperament. The simple capital denotes a well-developed mind, definitely artistic, from the printed capital, and inclined to elaboration, from the ornate capital, which also indicates a wavering between self-importance and an inferiority complex.

The dipping “g” shows a fanciful mood; the disconnected letters, a flow of thought with inspirational moods, with enough gaps to denote a poetic trend. The upright writing shows an analytical mind, with indifference to surroundings, a creature of whim or of the moment, considering the corroborative signs.

Most remarkable is the flourish, complex enigmatic, as though propounding a knotty problem, tangling the viewer, and then leaving him nowhere, with a final hook resembling a question mark. Typical of Poe, the father of the modern detective story. But this is in complete contrast to Franklin’s intricate but traceable flourish that ended in a neatly connected link denoted a satisfactory completion of whatever was at hand.

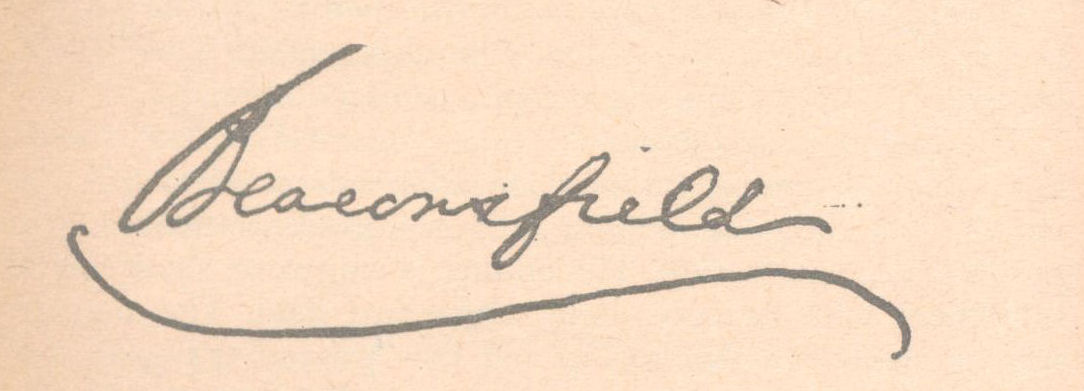

This is the signature of Benjamin Disraeli, after he became Earl of Beaconsfield. The high, distinctive letter B shows pride with a strongly individualistic nature. There is exactitude in the small letters, and their connected form shows energy and purpose, with a dash of ostentation or extravagance in the extension of the final letter.

Ambition is shown in the forward slant, indicating that Disraeli was still looking toward the future. Most graphic, however, is the line beneath. It combines the guarded nature of a strong statesman with the flowing curves of the literary skill for which Disraeli was also famous. It gives the impression of a firmness which is not inflexible.

(Footnote)The abbreviated “Benj,” though commonly used, was not universal at the time and might even be regarded as an affectation, particularly in Franklin’s case. Another signer, Benjamin Rush, a noted physician, used his full first name.

Leave a Reply