2.1 CARTOMANCY – THE ORIGIN OF PLAYING CARDS

CARTOMANCY OR FORTUNE TELLING WITH CARDS

****************************************

2.1 THE ORIGIN OF PLAYING CARDS

*******************************

Though the origin of playing cards is shrouded in the past, it is almost certain that they were originally designed to foretell the future, and they have been used for that purpose ever since they began. Some authorities claim that they evolved from Chinese divining sticks; others, that they were adapted from the pages of a legendary “Book of Thoth” used by ancient Egyptians.

Whichever the case, they were supposedly brought to Europe by wandering tribes of gypsies, some time after the year A.D. 1300. The gypsies presumably came from India by way of Persia, where playing cards of a picture type called “atouts” were already in vogue. The gypsies, to give themselves status, intimated that they were of Egyptian origin and spoke of their homeland as “Little Egypt,” so it would not be surprising if the Persian cards had been purposely attributed to Egypt instead.

There probably never was and never will be a gypsy camp without a pack of cards of some sort, and a member of the tribe who is capable of interpreting them. As for the cards themselves, the packs that first developed in Europe were called “tarots” and consisted of seventy-eight cards. Of these, fifty-six were suit cards similar to those of modern packs, except that the suits were swords, cups, coins, and rods, and that there were flour court cards to each suit, namely, king, queen, knight, and knave (jack). The “spot” cards, which bore the symbols mentioned, ran from ten down to one (ace).

|

|

|

|

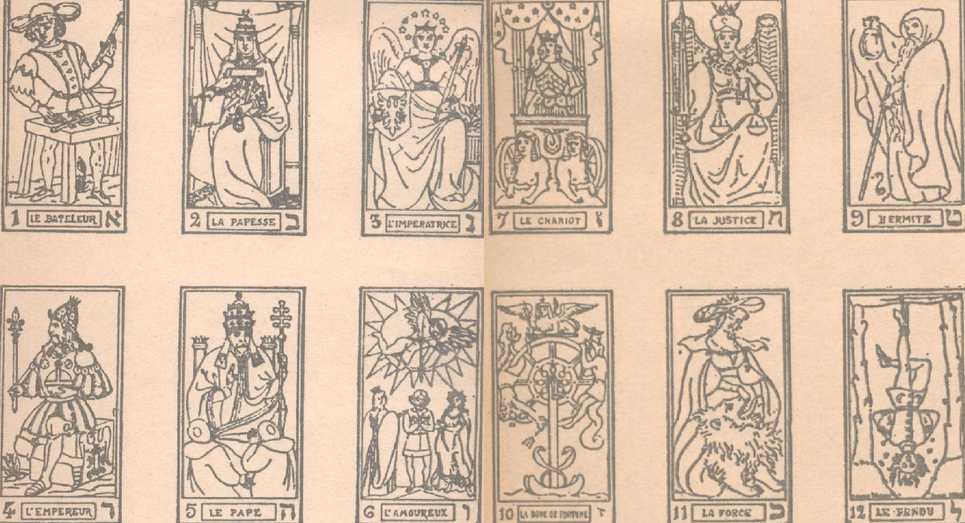

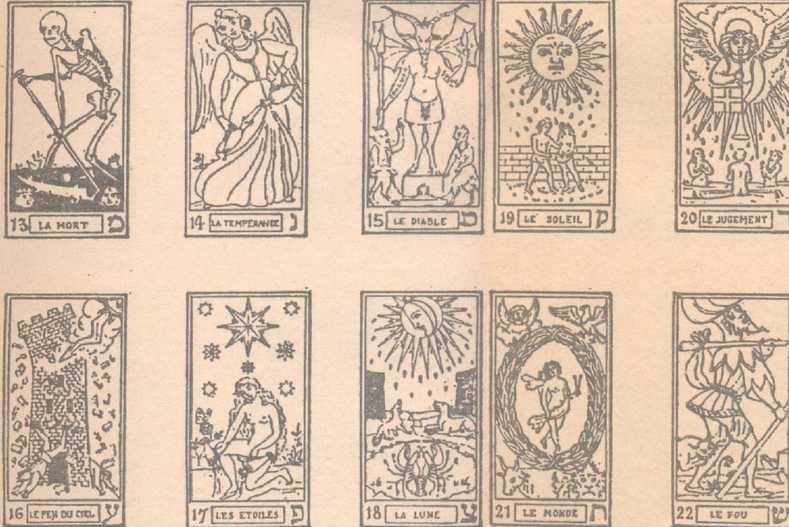

The additional twenty-two cards all bore symbolic pictures and corresponded to the atouts of the Persian packs. These cards were of various types, but generally speaking, they depicted similar personages and themes. One typical list ran as follows:

1. the juggler, 2. the high priestess, 3. the empress, 4. the emperor 5. the hierophant, 6. the lovers, 7. the chariot, 8. Justice, 9. the hermit, 10. Fortune, 11. Strength, 12. the hanged man, 13. Death, 14. Temperance, 15. the devil, 16. Lightning, 17. the stars, 18. the Moon, 19. the Sun, 20. Judgment, 21. the world, 22. the fool.

These cards constituted the “greater arcana” and each had its special divinatory significance. Since the pictures were upright, they were often inverted when dealt, chancing their interpretation, frequently for the worse.

The “suit” cards, swords, cups, coins, and rods, formed the “lesser arcana” and these had their own interpretations. Their original designs were also “one-way,” allowing them to be reversed when dealt, so that their readings could be variable.

In full form, these were used chiefly for telling fortunes, and when card games were developed, the pack was cut down to four suits, and four cards – the knights – were eliminated, reducing the pack to fifty-two cards.

In France, the suits were changed to spades, hearts, clubs, and diamonds. English and American cards adopted the new pattern, resulting in the playing cards of today. Oddly, one card managed to survive from trumps major, as the greater arcana was also known. That card was the fool, and it forms the joker of our modern packs.

These departures from the original tarots had little effect upon the card readers. They continued to interpret them in terms of past, present, and future, with the usual results. Mademoiselle Lenormand, a famous cartomancer during the Napoleonic era, was credited with some fantastic revelations which particularly impressed the Empress Josephine. At that time the pack popularly used in France was the thirty-two card piquet pack (aces down to sevens), and presumably she used those in some of her divinations.

With the development of “double-ended” court cards, the type now in vogue, it became impossible to note if they were reversed when dealt. Cards of French and English design always presented that problem with the diamond suit, which has spots that look alike both ways. The other suits, too, lost their reversible quality when printed with spots pointing opposite ways, like the two of spades, in modern packs.

One answer was to mark the “top” end of each card, thus telling when it was reversed. That course was adopted during the vogue of the thirty-two-card pack, which was used almost exclusively by many cartomancers who followed Mademoiselle Lenormand. But with the emphasis on games demanding a fifty-two-card pack, fortune-telling systems fell into the same groove, and today there are enough “full pack” methods to supply the demand. These eliminate all the nuisances and uncertainty of “reversed” card interpretations, which in some instances is an arbitrary factor. So in the pages that follow, you will find instructions for full pack reading exclusively, in conformity to the modern trend.

Devotees of the tarot pack still regard it with a sentiment akin to awe, but it is hard to share their view. The art of cartomancy lies more in the skill and insight of the interpreter than in the cards themselves. Mademoiselle Lenormand did right well with the cards of her day and followed it up by putting out her own fortune-telling pack, with her favorite instructions printed on the appropriate cards. Such packs have been printed ever since, some attributed to the Great Lenormand and others with titles of their own.

During the centuries, gypsies and other gifted folk have been reading whatever cards come to hand, whether tarots, circular cards of Hindu origin, or cards of various European countries with their different symbols. Readers can try their own hands with available cards and learn for themselves the spell of the unknown as revealed by the ever-changing pasteboards that could still be the mystic pages from the unbound Book of Thoth!

Leave a Reply